The Great Rolling Of The World

How amazing it is, that we learn to stand upright in the world, to walk through and with the landscape of our lives. Who hasn’t witnessed the triumph of a baby who lifts herself to her feet, for the first time, and steps into the world? The movement of all life shapes our walking bodies. And our walk—its pace, form, intention—shifts in response to physical, emotional, mental and spiritual stimuli. Take a look at the people around you and notice how differently each one walks, or even how your walk takes on subtle changes in speed, stride or lilt depending on the time of day, your mood, and the events happening in your life.

The verb walk as it is currently used and understood in English evolved through the merging of two distinct Old English verbs, both related to the German walken, “to knead, beat, thrash, press or mat together, toss about, ponder" (OED). The Old English walk, “to roll, toss, turn over”, mostly in reference to the movement of the Ocean, shifted in Middle English to “to move about, travel” (OED).

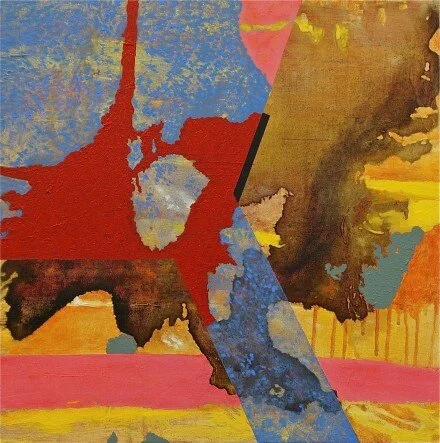

Expanse, Wesley Hurd

Most of the world’s religions and cultures have a great walking story. Jesus and the Buddha are both said to have walked on water. Many tribal communities send members on a Spirit walk of one kind or another. Walking has also gain traction in more recent years as a kind of activism for nearly every illness and malcontent of the modern world, as Kate Murphy covered in The New York Times. Similarly, Walt Whitman evokes a gestalt of great-world-rolling in his poem, “There was a Child went Forth,” from Leaves of Grass:

THERE was a child went forth every day;

And the first object he look’d upon, that object he became;

And that object became part of him for the day, or a certain part of the day, or for many

years, or stretching cycles of years.

The early lilacs became part of this child,

And grass, and white and red morning-glories, and white and red clover, and the song of

the phoebe-bird,

And the Third-month lambs, and the sow’s pink-faint litter, and the mare’s foal, and the

cow’s calf,

And the noisy brood of the barn-yard, or by the mire of the pond-side,

And the fish suspending themselves so curiously below there—and the beautiful curious

liquid,

And the water-plants with their graceful flat heads—all became part of him.

The field-sprouts of Fourth-month and Fifth-month became part of him;

Winter-grain sprouts, and those of the light-yellow corn, and the esculent roots of the

garden,

And the apple-trees cover’d with blossoms, and the fruit afterward, and wood-berries,

and the commonest weeds by the road;

And the old drunkard staggering home from the out-house of the tavern, whence he had

lately risen,

And the school-mistress that pass’d on her way to the school,

And the friendly boys that pass’d—and the quarrelsome boys,

And the tidy and fresh-cheek’d girls—and the barefoot negro boy and girl,

And all the changes of city and country, wherever he went.

His own parents,

He that had father’d him, and she that had conceiv’d him in her womb, and birth’d him,

They gave this child more of themselves than that;

They gave him afterward every day—they became part of him.

The mother at home, quietly placing the dishes on the supper-table;

The mother with mild words—clean her cap and gown, a wholesome odor falling off her

person and clothes as she walks by;

The father, strong, self-sufficient, manly, mean, anger’d, unjust;

The blow, the quick loud word, the tight bargain, the crafty lure,

The family usages, the language, the company, the furniture—the yearning and swelling

heart,

Affection that will not be gainsay’d—the sense of what is real—the thought if, after all,

it should prove unreal,

The doubts of day-time and the doubts of night-time—the curious whether and how,

Whether that which appears so is so, or is it all flashes and specks?

Men and women crowding fast in the streets—if they are not flashes and specks, what

are they?

The streets themselves, and the façades of houses, and goods in the windows,

Vehicles, teams, the heavy-plank’d wharves—the huge crossing at the ferries,

The village on the highland, seen from afar at sunset—the river between,

Shadows, aureola and mist, the light falling on roofs and gables of white or brown, three

miles off,

The schooner near by, sleepily dropping down the tide—the little boat slack-tow’d

astern,

The hurrying tumbling waves, quick-broken crests, slapping,

The strata of color’d clouds, the long bar of maroon-tint, away solitary by itself—the

spread of purity it lies motionless in,

The horizon’s edge, the flying sea-crow, the fragrance of salt marsh and shore mud;

These became part of that child who went forth every day, and who now goes, and will

always go forth every day.

Like the modern pilgrim-activist in Murphy’s article, the child in Whitman’s poem both shapes and is shaped by the world. This mutuality gives rise to the central question of the poem— Whether that which appears so is so? Whitman’s question is the question, the one that drives us as a species in search of an answer, a cause, a meaning that animates and illuminates our lives. We embody this quest in the way we walk through the world. Consider a few of the movement-rich verbs in Whitman’s poem: suspending, staggering, yearning, swelling, crossing, falling, dropping, slapping, flying.

The movement of the poem itself can be understood as the answer to Whitman’s question. Perhaps this is the fullest answer we can grasp, the one that is always only partial and continually revealed to us through our individual and collective tumbling, thrashing and staggering, the great rolling that is the going forth, each day.