The Undying

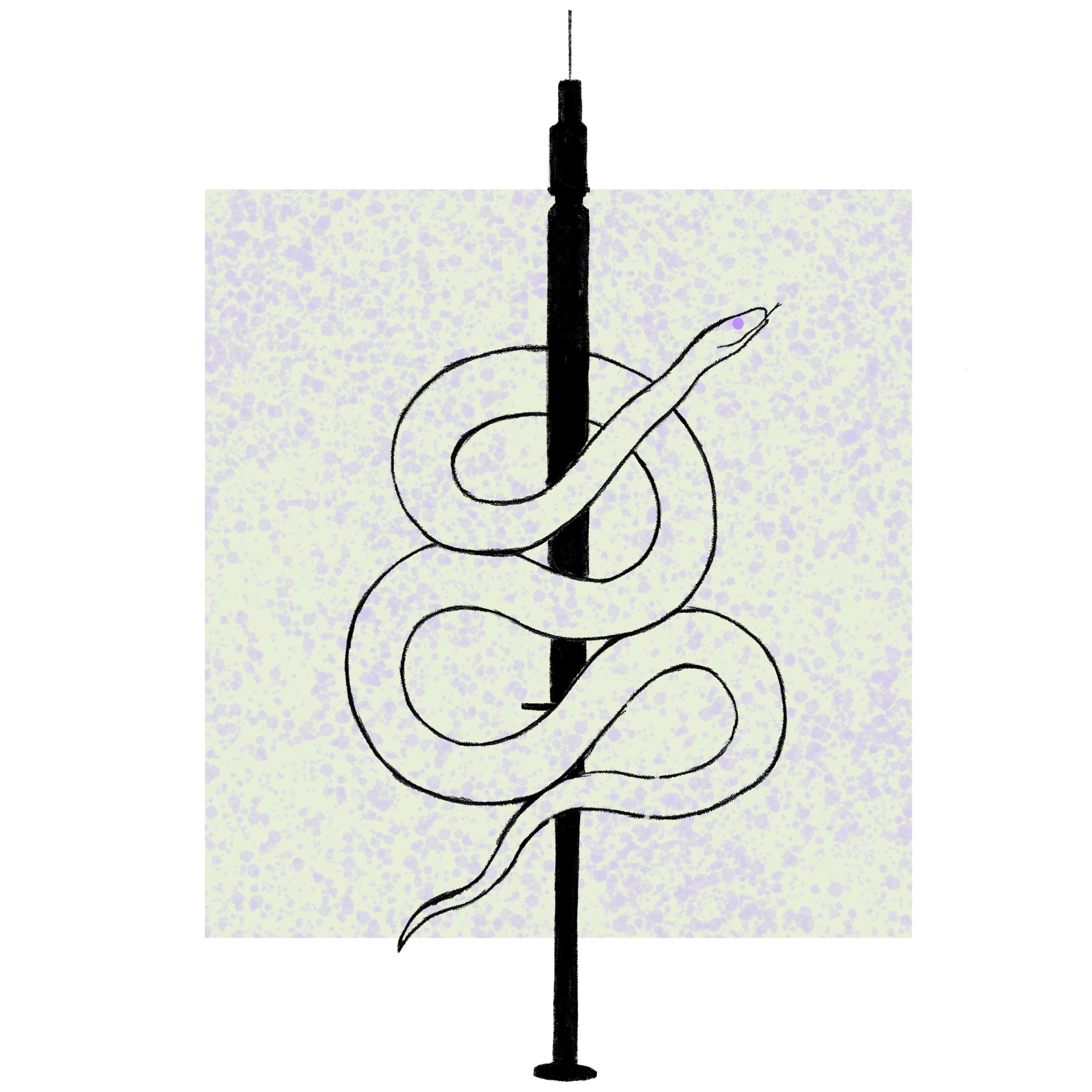

In 2014 Ann Boyer was 41 years old. She was a single mother. She was a poet. A friend. A lover. She was also in possession of a large tumor located in her right breast, triple-negative breast cancer. She was to survive. The Undying is her narrative, not just of survival, but of all the deaths, indignities and irrevocable changes that comprise the experience of having cancer and treating it, of almost dying from it and living to tell about it in modern America.

Boyer’s book is in dialogue with the women writers who have come before her in telling the tale of a primarily female cancer: Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor, Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals. But she is clear in her first few pages that “the silence around breast cancer that Lorde once wrote into is now the din of breast cancer’s extraordinary production of language. In our time, the challenge is not to speak into the silence, but to learn to form a resistance to the often obliterating noise” (8).

Some of the noise is literal, such as the communal cancer “pavilions” where Boyer and others like her receive treatment without beds, privy to others’ crying and vomiting, to the voices of doctors who casually disclose the often life threatening side effects of treatment just before its delivered. Also, to the silence left in the wake of those who disappear from a cancer patient’s life, who can’t handle the cruel transformation of a body on the brink, one that disappoints the culturally fashioned narrative of “celebrity survivor, smiling before the surgery and smiling after, too, bald and radiant and funny and productively exposed” (78).

So much of the art of The Undying is Boyer’s ability to juxtapose the personal and the collective, the now and the historical. Or perhaps more than juxtapose, to point in the direction of relationships that are ungraspable but felt and that define both the macro and the micro. It seems telling that most of the literary references and images Boyer draws on to understand her own experience come from a more distant past. This allows for the narrative to take on depth and texture, to wave out into more philosophical territory about the role of language and time in shaping both illness and death. In this way, Boyer’s own cancer is a story about Cancer, a story about the inevitability of pain, illness and death. Most everyone is carrying around some cancer.As Boyer puts it, “Cancer doesn’t really exist, at least not as itself. Cancer is an idea we cast as an aspersion over our own malignancy” (140).

Alongside Boyer’s sharp critique is the playful, the creative, the subversive, no less essential to her story and perhaps critical to her survival. Boyer imagines writing a beautiful book against beauty, plans for a kind of public monument to weeping, where “anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment” (205). She makes plans to distribute vocabularies of pain that express more than a clinically numbered scale, each starting with an Emily Dickinson poem. And she buries parts of her Your Oncology Journey binder in public places, sprinkled with kale seeds. As Boyer reflects at her lowest, “what I needed most was art—not comfort—and so it was to get through cancer that I had to wish everything around me into aesthetic extremity” (387).

This aesthetic extremity is everywhere in Boyer’s book but it never fetishizes suffering; it gives life, both in and outside the narrow grasp of death, a vitality often hidden, subjugated by systems, but available to language and deeply felt.